The year is 1981. It is a world without the internet, a world without social media, a world without the Amber Alert. It is a time when children played outside, unbound by digital leashes, their only curfew the failing light of the afternoon sun. It was in this world, in a quiet, unassuming town, that a family’s world did not just crumble—it was stolen, in broad daylight, in a span of minutes.

This is the story of the day the earth seemingly opened up and swallowed three children. Not just any children. Three siblings. Three “kambal” siblings—triplets, born minutes apart, a local miracle. One moment, they were a flurry of laughter and motion in their front yard. The next, they were a ghost story, a wound that has refused to close for more than four decades.

For the purpose of this story, we will call them the Rosales Triplets: Juan, Julio, and Josefina. They were four years old. They were, as their now-elderly mother, Aling Nena, recalls with a pain that is still raw, “one soul in three bodies.” They shared a language of their own, a secret bond that only multiples seem to possess.

It was a hot, dusty afternoon in a province where nothing ever happened. Aling Nena was inside, preparing merienda. The sound of her children playing in the fenced-in yard was the soundtrack to her life. It was a constant, happy noise, a reassurance that all was right in their small, simple world.

Then, the sound stopped.

It is a sensation that every parent dreads—the sudden, unnatural silence. It is a vacuum that pulls all the air from your lungs. Aling Nena would later tell police she had been inside for “no more than five minutes.”

She wiped her hands on her apron and called their names. No answer. She called again, a little louder, a flicker of annoyance in her voice. “Juan! Julio! Fina!”

The silence that answered her was a physical thing. It was heavy, wrong.

She ran to the door and looked out into the yard. The gate, which she had latched that morning, was slightly ajar. The yard was empty.

This is the moment that has played, on repeat, in her mind for 43 years. The disbelief. The cold, sharp spike of panic. The desperate, rising scream. Neighbors came running. The search began within minutes. It was a frantic, disorganized sweep. The entire barangay was on its feet, scouring ditches, backyards, and the nearby sugarcane fields.

But how do you hide three children? How do you take them, all at once, without someone seeing, without someone hearing a cry?

The 1981 police investigation was a study in frustration. With no technology and limited resources, officers were baffled. There was no ransom note, which immediately threw the “kidnapping” theory into question. No disgruntled family members, no suspicious vehicles, no physical evidence. It was, for all intents and purposes, a perfect crime.

The police were faced with an impossible puzzle. To take one child is a risk. To take three, all at once, is a logistical nightmare. It suggests planning. It suggests more than one person. It suggests a motive that was darker and more complex than a simple crime of opportunity.

As days turned into weeks, the theories became more frantic. A local “albularyo” (folk healer) was consulted, claiming the children had been “taken by the elementals” of the nearby forest. A grieving, desperate Nena and her husband, Mang Arturo, clung to this, leaving offerings of food and candy at the base of a large balete tree, begging for their children’s return.

But the real monsters, as we know, are human.

The weeks turned into months. The months turned into years. The national news forgot them. The police, with no leads, moved the case from “active” to “cold.” But for Nena and Arturo, time stopped.

How do you mourn a ghost? How do you grieve for a loss that has no finality? Their lives became a living purgatory. They kept the children’s bedroom exactly as it was. Three small, identical beds. Three sets of clothes laid out. A shrine of hope that slowly, agonizingly, became a museum of pain.

The passage of time is a cruel thief. It stole Nena’s youth and Arturo’s strength. It turned their black hair to silver. It etched deep lines of sorrow into their faces. But it could not steal the one thing that kept them alive: a desperate, burning hope that one day, their children would come home.

For 40 years, the case of the Rosales Triplets was a local legend. A story to frighten children. “Don’t wander off,” parents would say, “or the people who took the ‘kambal’ will get you.”

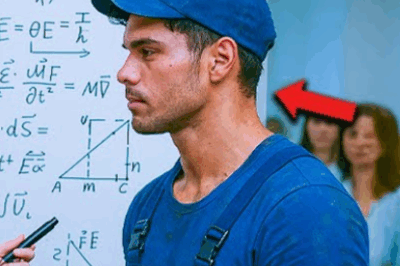

Then, two years ago, something happened. A new investigator, a cold-case detective from the city, stumbled upon the file. He was haunted by the sheer impossibility of it. Three children. Triplets.

The new theory that has emerged is chilling and all too plausible in the 1980s Philippines, a time of chaos and shadow economies. The detective does not believe it was a kidnapping for ransom. He does not believe it was a crime of passion.

He believes it was a “kidnapping to order.”

He paints a horrifying picture of a sophisticated, illegal adoption ring. A ring that provided children to wealthy, childless couples, both in the Philippines and abroad. The triplets, with their identical, cherubic faces, would not have been seen as three children. They would have been seen as a “set.” Or, even more tragically, as three individual “products” to be sold to three different families.

This theory explains the silence. It explains the lackt of a ransom. It explains the professionalism of the abduction. The children were not harmed; they were harvested.

This theory has re-opened the wound, but it has also brought a new, focused agony. The detective has been carefully cross-referencing birth records, adoption papers, and immigration documents from 1981 to 1983. He is looking for a phantom, a whisper, a statistical anomaly.

It also raises the most heartbreaking questions of all.

Are Juan, Julio, and Josefina still alive? They would be 47 years old. Do they have any memory of their real parents? Do they know they are Filipino? Do they know that they are triplets?

Or were they separated, raised in different countries, under different names, their entire identities erased? The thought is almost too much to bear. The idea of three siblings, bound by blood and birth, living out their lives as strangers, unaware that the other two even exist.

The YouTube video, “TATLONG MAGKAKAPATID NA KAMBAL NAWALA TAONG 1981,” is part of a new, desperate plea from the family, aided by this new investigation. They are using the very technology that did not exist in 1981 to solve the crime. They are hoping that someone, somewhere, will see an old photo. That a 47-year-old man in America, or a 47-year-old woman in Australia, might feel a sudden, inexplicable jolt of recognition. That they might look in the mirror and see a face that matches two others.

Aling Nena, now in her late 70s, sits on her porch. Her husband, Arturo, passed away five years ago, his last words a whispered plea to his wife: “Find them.”

“I know they are alive,” Nena says, her voice a thin, reedy whisper, but her eyes bright with an unshakeable conviction. “A mother knows. I feel them. I just want… I just want to see them. Before I close my eyes. I want to tell them that we never, not for one second, ever stopped looking.”

The yard is quiet. The gate is new, padlocked. But for Aling Nena, it is still 1981. And she is still listening, listening for the sound of three small voices, a sound that has been absent for a lifetime. The search, after 43 years, is not over. It has just entered a new, desperate, and final chapter.

News

Ang Babala sa Araw ng Kasal

Ang musika ng organ ay umalingawngaw sa loob ng Manila Cathedral. Ang bawat sulok ay pinalamutian ng libu-libong puting…

Ang Hapunan ni Sultan

Ang Mansyon de las Serpientes ay hindi isang ordinaryong tahanan. Ito ay isang dambuhalang monumento ng kapangyarihan ni Don…

Ang Halaga ng Isang Tasa

Ang “The Daily Grind Cafe” ay isang maliit na isla ng karangyaan sa gitna ng magulong abenida ng Maynila….

Ang Kontrata ng Kaluluwa

Ang amoy ng mamahaling pabango at lumang kahoy ay hindi kailanman umabot sa basement ng mansyon ng mga Elizalde….

End of content

No more pages to load