In the ruthless arena of national politics, perception is currency. A politician’s image, cultivated over decades, can be shattered in an instant. For years, Senators Panfilo “Ping” Lacson and Vicente “Tito” Sotto III built a formidable brand. They were the stalwarts of the Senate, the seasoned veterans, the supposed watchdogs against corruption. Lacson was the tough-as-nails, no-nonsense lawman. Sotto was the pragmatic and experienced legislative leader. Together, they projected an aura of integrity.

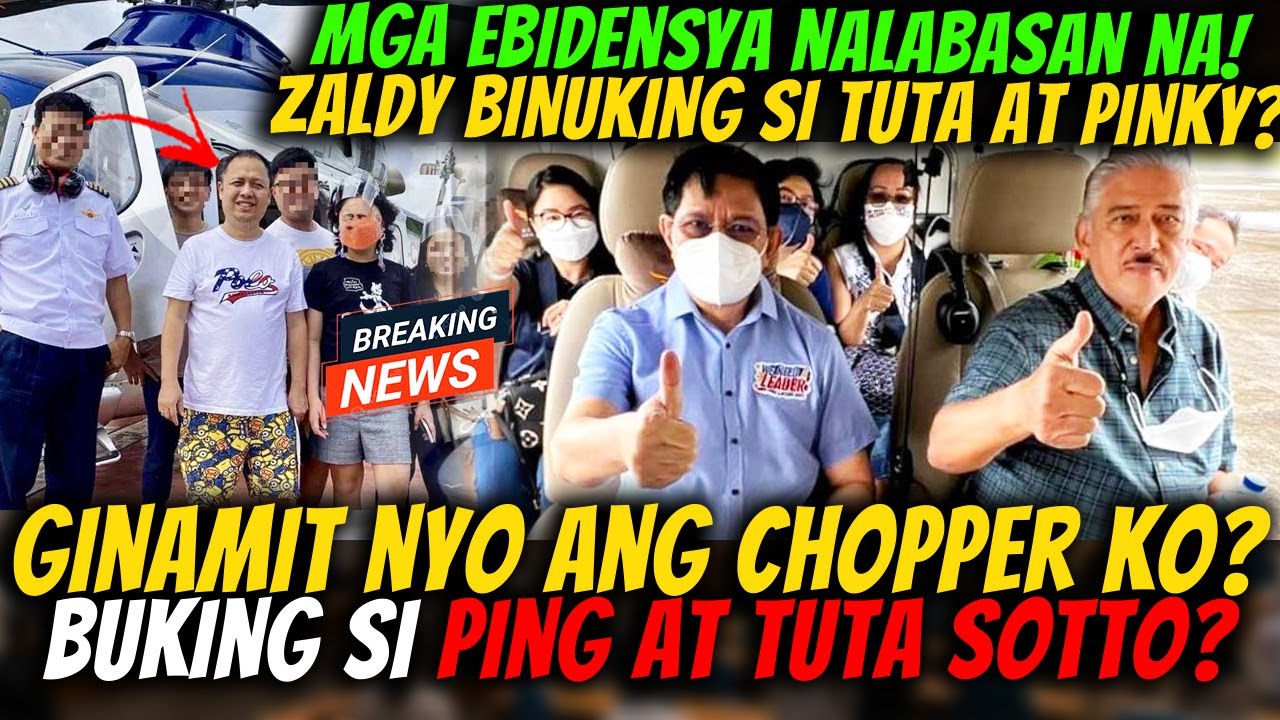

But a damning “bukingan”—an exposure—has ripped through that carefully crafted facade, raising devastating questions about their judgment, their alliances, and their true allegiances. The allegation is as simple as it is explosive: the duo allegedly used a private helicopter owned by Zaldy Co, a controversial businessman and political figure whose name has been entangled in some of the nation’s most questionable government dealings.

This isn’t just a story about a helicopter ride. It’s a story about a perceived betrayal, a conflict of interest so blatant it borders on arrogance. It’s a narrative that suggests the very men who claimed to be fighting the system were, in fact, benefiting from it.

The Backdrop: A Nation in Crisis

To understand why this revelation is so catastrophic, we must return to the context in which it surfaced. These allegations gained traction during a period of immense national suffering. The country was in the grips of a devastating public health crisis. Billions of public funds were being allocated for emergency response, and with that money came the stench of corruption.

The most infamous of these was the Pharmally scandal. Billions of pesos were allegedly siphoned into the pockets of a newly formed, under-capitalized company with shadowy backers. The Senate, with Lacson and Sotto as two of its most senior members, was front and center in investigating this colossal misuse of public funds. They were the faces of accountability, grilling witnesses and promising to get to the bottom of the rot.

The public, locked in their homes and facing economic ruin, watched these hearings with a mix of anger and desperate hope. They were looking for heroes. They were looking for leaders who were truly on their side.

It was against this backdrop of public fury and economic hardship that the “bukingan” occurred. The secret was out: the very senators posturing as anti-corruption crusaders were allegedly rubbing elbows with and accepting favors from figures linked to the very system they condemned.

The Men at the Center of the Storm

Ping Lacson and Tito Sotto: Their political partnership was the stuff of legends. They were a packaged deal, running for the two highest offices in the land on a platform of “Katapangan, Kakayahan, at Katapatan” (Courage, Competence, and Honesty). Lacson, in particular, built his entire career on an incorruptible, “Mr. Clean” image. He famously refused his “pork barrel” allocations, projecting himself as a man above the dirty transactions of politics.

Zaldy Co: On the other side of this equation is Zaldy Co. A powerful businessman and congressman, Co’s name has been persistently linked to massive government contracts and political influence. His enterprises have faced scrutiny over their involvement in multi-billion-peso projects, leading many to view him as a symbol of the powerful, entrenched interests that thrive on government connections. His association with the Pharmally controversy, even indirectly, placed him firmly in the public’s crosshairs.

The Allegation: More Than Just a Free Ride

The claim is simple: Lacson and Sotto used a helicopter owned by or linked to Zaldy Co for their travels.

To the average person, this may seem minor. Politicians need to travel, and private transport is efficient. But in the world of politics, there is no such thing as a free ride.

This act, if true, represents a catastrophic lapse in judgment. It’s not just about optics; it’s about ethics. How can senators investigate massive government scandals when they are accepting favors from an individual who is a significant player in that very sphere?

It feeds a narrative that critics have long pushed: that Lacson and Sotto, despite their posturing, are not independent. The source material’s use of the word “tuta” (puppet) is harsh, but it captures the public’s fear: that their leaders are not working for them, but are instead beholden to wealthy benefactors who pull the strings from behind the scenes.

This allegation transforms them from independent watchdogs into “trapo”—traditional politicians—who say one thing in public and do another in private. It suggests their crusade against corruption was selective, a performance for the cameras while they enjoyed the perks of power behind closed doors.

The Inevitable Denials and the Public’s Verdict

When confronted, the defense from politicians in these situations is predictable. They often claim the transport was offered by “friends and supporters” and that “no public funds were used.” They may attempt to distance themselves, claiming they were unaware of the helicopter’s true ownership or that their relationship with the individual is purely personal and has no bearing on their public duties.

But this defense crumbles under scrutiny. In politics, especially at that level, plausible deniability is a shield that rarely holds. The question isn’t whether it was illegal; the question is whether it was right.

For a public that was sacrificing daily, the image of their leaders enjoying the luxury of a private helicopter—paid for by a controversial tycoon—is a slap in the face. It reinforces the deeply cynical belief that all politicians are ultimately the same, that the entire system is a club, and the public is not invited.

The “bukingan” didn’t just expose a flight; it exposed a massive disconnect. It revealed a political class that seemed to believe it could operate by a different set of rules.

The Lasting Damage: An Erosion of Trust

This scandal’s true casualty is trust. It permanently stained the “clean” records that Lacson and Sotto spent their entire careers building. For Lacson, the man who prided himself on integrity, the association is particularly damaging. It provided ammunition to his critics, who had long accused him of being a “secret” ally of the very forces he claimed to fight.

For Sotto, the pragmatic leader, it made him look careless and compromised, willing to overlook ethical lines for the sake of convenience.

This controversy serves as a brutal lesson in modern politics. In an age of instant information, secrets don’t stay secret for long. A “bukingan” can come from anywhere, and when it does, it can undo a lifetime of work.

The story of the chopper, Zaldy Co, and the two senators is a microcosm of a larger national struggle. It is the story of a public yearning for genuine leaders, constantly being disappointed by men who promise change but practice the same old, dirty politics. The secret is out, and it has left an indelible mark on the political landscape, reminding us that the road to genuine public service is fraught with temptations, and that the currency of perception, once lost, is almost impossible to regain.

News

A “Whistle-Show” or the Truth? Congressman Saldiko’s 100 Billion Bombshell Against Marcos Riddled with “Plot Holes”

In the high-stakes theater of national politics, a new drama has captivated and confused the public. A sitting congressman, known…

Ang Tatu na Sumira sa Lahat: Pagtataksil sa Bolinao, Nagtapos sa Korte at Kulungan

Noong Nobyembre 2015 sa Dagupan, Pangasinan, isang tricycle ang huminto sa tapat ng bahay ng pamilya Molina. Mula roon ay…

DUROG NA PUSO NG ISANG OFW: ASAWA AT SARILING AMA, NAHULING NAGSASAMA SA ISANG KUBO; HUSTISYA, NAKAMIT MATAPOS ANG MATINDING PAGTATAKSIL

Para sa maraming Overseas Filipino Worker (OFW), ang bawat butil ng pawis na tumutulo sa ilalim ng mainit na araw…

A Web of Deceit: Senator Marcoleta Alleges Massive Conspiracy Involving Judiciary, Malacañang in Multi-Billion Scandal

A firestorm of controversy is ripping through the Philippine Senate, and at its center is a multi-billion-peso flood control scandal…

Silence Broken: Jimmy Santos Unleashes Decades of Alleged ‘Betrayal’ and ‘Mistreatment’ by TVJ

The foundations of Philippine showbiz are shaking. What began as a startling revelation by former host Anjo Yllana has now…

‘He Knew the Stench Was Coming’: Saldico Unleashes Receipts, Claims 100B Insertion Was Marcos’s Order

In a political firestorm that threatens to engulf the highest levels of government, former Ako Bicol Representative Saldico has dropped…

End of content

No more pages to load